Recent news about a 6 year-old boy bringing a gun from home and shooting his first grade teacher in the classroom is horrifying and tragic for all involved. Most of us probably asked how could that happen and what can be done about it? Why is violence in our country escalating? So I consulted a good friend who is a licensed mental health and school counselor for children and began reading about the common causes of violence in young children. It is a complex topic. There is no single pathway sufficient to explain the development of abnormal aggressive behavior and its correlation with violence in adults, nor why some children are resilient. However, it is important to address it in early years before an irreversible behavior pattern becomes dominant.

Aggression vs Violence

The origins, meaning and development of aggression in children under 12 (age of full reasoning and abstract thought) are multiple and not all negative or harmful. It may even be considered just a part of growing up when dealing with a two-year old’s tantrums. It may be excused in a child born with neurological or cognitive disabilities. It may be seen as a variation in temperament or necessary defense. There are natural differences between boys and girls. It may not have any intention to harm someone. During the preschool years, children may resort to physical expression of irritation, frustration or anger by pushing a playmate or grabbing a toy without intentional harm.

Aggression and violence are not the same, although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. Violence involves the use of force with intent to injure another person or damage property. Violence can target an individual or a group, be sexual in nature or occur following the use of alcohol or drugs. Aggressive behavior involves angry, retaliatory or dominating actions but is not necessarily violent. Its expression varies with age and gender. Aggression is a common human behavior and acceptable in some cultures more than others. It is normally a result of negative feelings such as anger, frustration, injustice, vulnerability or superiority. Aggression is linked with brain chemicals like low serotonin and high testosterone levels.

For the purpose of this paper, I shall use the following definition of aggression: an act directed toward a specific other person or object with or without intent to hurt or frighten, keeping in mind that intent is more subjective than observed behavior. Problematic aggression is related to a lack of impulse control or emotional regulation for an appropriate developmental age. Its symptoms change with developmental motor and cognitive competence. The onset of aggression can be seen by the age of 2 to 3 years in boys and a bit later in girls. More serious violence tends to increase with age, especially during adolescence. Aggression in early life is predictive for later violence but not by 100 percent; late onset of violence does occur in a minority of offenders with no known childhood history of maladaptive aggression.

There are four main types of aggression. Accidental aggression is not intentional, may be the result of carelessness, and often occurs during play of young children. Expressive aggression is intentional but not meant to cause harm, such a throwing toys or knocking down things. Hostile aggression is meant to cause either physical or psychological pain, such as bullying. Instrumental aggression occurs when children fight over objects, territory or rights, and in the process, someone gets hurt. Most of aggression between the ages of 2 and 6 is instrumental as a result of struggles over toys or materials. Toddlers and preschoolers are naturally impulsive, have limited language skills and are egocentric so tend to hit, grab or kick to get what they want at times.

Development of Prosocial Behavior vs Aggression in Young Children

The manifestation of aggression changes dramatically as the child moves through the developmental stages with the expression differing for each gender. While boys may use physical force, grabbing objects or animal cruelty, girls are less direct with name calling, criticizing, alienation, or character defamation. Some aggression is normal, particularly in boys, and considered healthy self-defense. Cultural norms do play a role in what is acceptable or encouraged. Playful fighting must be distinguished from hostile intentions. Associated traits include difficult temperaments in infants, poor emotional regulation, poor impulse control, low intelligence, reading and verbal problems, inattention, hyperactivity, feelings of social rejection and inflated egos. The establishment of an aggressive behavior pattern is one of the best predictors of continued aggression and violence.

As will be described below, aggression and violence can be learned behavior patterns that are incorporated into an individual’s internal programming and self-regulation systems. Cognition, social reasoning and moral development play central roles in aggressive and violent behavior, unless blocked by underlying problems and barriers of mental processing. As a child ages and develops, patterns of judgement and decision making about standards of conduct are formulated and stabilized over time.

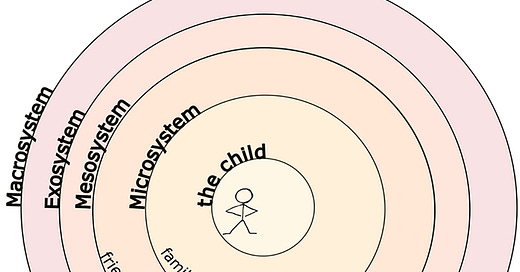

Social and moral programming is taught not only by parents, but by families, peers, schools, religious organizations, TV and movies, media, books, and sports coaches. Children learn how society is organized, ruled, what is acceptable, and what is right and wrong through all these sources and the environment they live in. Learning determinants include biological abilities, temperament, knowledge level, natural developmental processes, experience and social variables. Social reasoning is the process of learning acceptable behavior, drawing inferences about the intentions and behavior of others, and regulating one’s own actions. Prosocial decisions require cognition, empathy, cooperation, and desire for positive relationships.

Childhood Developmental Stages

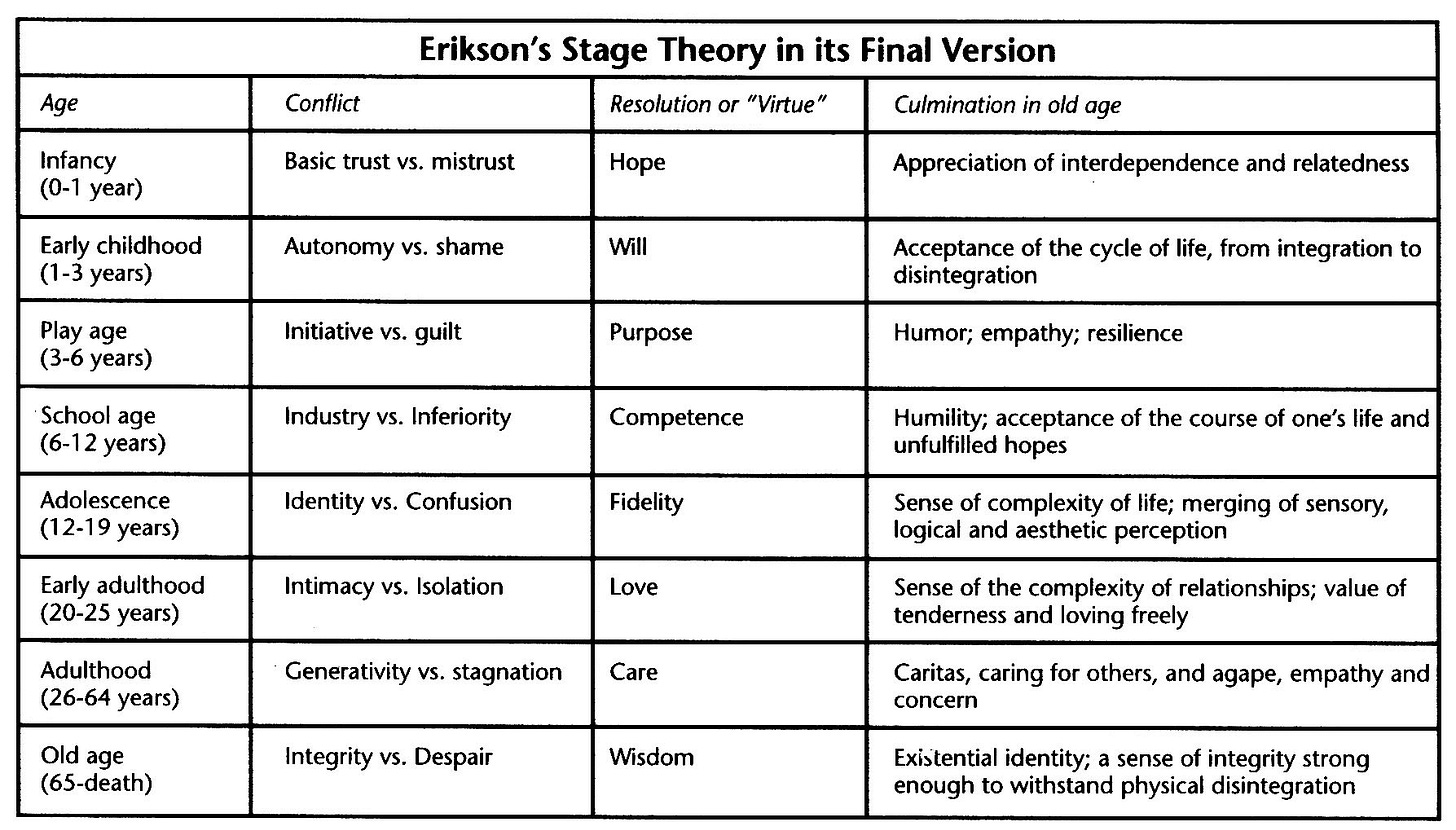

Comprehending childhood behavior and attitudes requires an understanding of developmental levels. Erik Erikson’s Eight Stages of Psychosocial Development provides useful insights by describing key conflicts and milestones from Birth to over age 65. Childhood milestones are very important steps in learning about the self and the world with life-long impacts.

In Stage 1, the parents provide basic needs such as feeding, teaching the infant that they can be depended upon, which builds a sense of trust, security and safety in facing the world. But if the parents are unpredictable or unreliable, the child needs will not be met and will look at the world with anxiety, fear and mistrust. Attachment to the mother or primary caregiver is the most significant relationship.

In Stage 2, the toddler begins to assert independence and can do some things by himself. This helps the child to feel secure in his own abilities. Without that, the child will feel self-doubt and inadequate to face the world. The parents are the most significant relationships. Toilet training and learning to get dressed are milestones.

In Stage 3, during the preschool years, the child interacts socially, plays with other children, uses tools and makes art. He learns to take initiative, explore and control what happens. He develops self-confidence and enjoy having a purpose. The entire family provides the most significant relationships. If the parents are over controlling or non-supportive, the child may lack ambition or be filled with guilt.

In Stage 4, the elementary school age child’s key relationships expands to teachers and peers. He compares himself to others, engages in sports, learns math, science and concepts of space and time. He is able to start contributing to the world and make a difference. He gains flexibility in understanding cultural differences. By developing senses of competence, pride and accomplishment, he learns to be industrious and set goals. Negative experiences such as ridicule or punishment can lead to feelings of inferiority.

Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development is a widely accepted perspective of how children learn to think logically. He believed that the 4 stages always happen in the same order and must be accomplished through the assimilation of experiences before moving on to the next stage. Age 12 is still used as a legal age of reason.

Elliot Turiel’s Domain Model of Social and Moral Reasoning in 1983 provides important empirical research for understanding the development of social and moral reasoning in children and adolescents and its links to aggressive behavior. He and other psychology researchers found that by the age of 3 years, children demonstrate consistent patterns of reasoning and making distinctly different judgments in four cognitive domains of social, moral, personal and prudential situations. Individual children of all ages learn to make interpretations based on the selected domain in a parallel manner rather than a hierarchal step-wise manner. In complex situations, knowledge and experience is drawn from more than one domain, but are prioritized differently.

· Personal domain: how an issue or event impacts the self, autonomy and individuality.

· Social conventional domain: understanding of social norms and expectations for smooth interpersonal functioning and relationships.

· Moral domain: recognition of human rights, welfare, and fairness for others; principles of how individuals should treat each other.

· Prudential domain: how personal safety is impacted

There are three types of early childhood everyday play providing experience in which reasoning develops. Harmful events are when a child uses force against another such as hitting someone. Disorder events are when the child creates a material disorder such as spilling food, which is viewed as an inconvenience with no damage or harm done. In Joint play with others there are natural and unavoidable outcomes.

The family is the primary arena for induction into social life in young children and infants and can be a place of conflict as well as resources and support. Family members live in a give-and take constellation of competing interests where aggression can occur. It is a place where some children resort to tantrums, hitting and shouting, so can be seen by parents as irritable and difficult to control. It is a task of the parents to use those opportunities to teach children prosocial techniques and emotional regulation early in life.

Children’s reasoning about the seriousness of a transgression or the amount of deserved punishment for a transgression is contingent upon the situation context, or social domain. Moral transgressions are consistently identified as wrong, even in the absence of a specific rule. In contrast, judgements about social conventional transgressions are more specific, such as whether an authority figure was present or made the rule. Children judged even minor moral transgressions, such as stealing an eraser, as more wrong than major social transgressions such as wearing pajamas to school. Children ranked moral transgressions as “more wrong” than social conventional transgressions, and both types as “more wrong” than rules regarded as personal choice or affecting only the individual. Young children consider physical harm worse than property damage, although both are in the moral domain.

When questioned about typical transgressions, children were rarely prepared to argue with their mother over moral, social conventional or prudential issues but made frequent challenges to their parent over personal issues. Likewise, children regard transgressions of mothers’ rules as more serious than transgressions of teachers’ rules.

The personal domain is comprised of social actions that individuals deem to be within their own personal control and without impact on others or society in general. Choices of friends, physical appearance and whether or not to use drugs is considered within the realm of personal preference by both drug users and non-drug users. Actions within this domain are least often considered wrong.

Age related changes in social reasoning occur, indicating on-going development within each domain. For example, 6 to 7 year-olds made more rigid decisions based on domains ignoring outcomes more so than 10 years-olds. There were also age related, developmental differences in the salient interpretation of mixed domain situations. Oder children judged moral transgressions to be wrong irrespective of whether an authority figure permitted or prohibited the event. This was in contrast to younger children who more frequently prioritized the social conventional aspect of the transgression if an authority figure was involved. This is likely related to teachers and parents discussing harm and fairness to others with children regarding moral issues, but focusing on rules when discussing social convention norms of behavior.

Regulation of aggressive acts would generally fit into the moral domain of social reasoning because of harm to others. And children as young as 3 consider issues of harm and others’ welfare to be wrong, independent of rules and authority. This leads to the suggestion that children who consistently display aggressive behavior may be interpreting and categorizing events differently from non-aggressive children.

Three psychology researchers, Guerra, Nucci, and Huesmann, presented their Integrative Model of the Relation Between Moral Cognition and Aggression around 1994, built upon Turiel’s Social Reasoning Domain Theory. The premise is that moral and social development is multifaceted and not simply determined by stage of development. The Domain Model provides a connection between moral stage, information processing, decision making and moral action. The term, moral cognition, is used to differentiate judgments about moral issues such as fairness or causing harm from non-moral issues such as mathematics.

According to cognitive development moral theories, moral action cannot be understood independent from the actor’s thoughts and judgments about that action. Social learning theories stress the importance of beliefs about standards of conduct and outcome expectations. Based on the consequences of aggressive behavior, young children learn to discriminate between acceptable and non-acceptable behavior and regulate their behavior accordingly, using whatever adaptive and problem skills they have.

Cognitive expectations of negative consequences and external sanctions for aggressive behavior generally are inhibiting. The context of the situation and the degree of importance attached to the outcomes are also factors. Many situations are complex involving more than one domain’s dilemmas, so the individual draws knowledge for decision making based on stage of development, beliefs, social, personal and gender biases, and salience of situational clues.

The model authors proposed the following conclusion regarding contextualized judgments and aggressive behavior: Aggressive actions are directed by judgments which may draw primarily from the moral knowledge system or may entail reasoning from the personal or conventional domains, although preliminary studies suggest that aggressive behavior may be characterized by an overextension of the personal domain. The resulting judgments will be a function of the degree to which various knowledge systems are invoked and the level of development within those systems.

Risk Factors For Childhood Aggression and Violence

The origins of aggressive behavior in early years have multiple determinants, rather than any single cause. It is not uncommon for a child referred for mental health problems to have more than one diagnosis, which guides treatment.

Aggression can be conceptualized as inherent to the individual, as a family problem, or a social problem. Violence against others and suicides are epidemic. American behavioral health systems tend to classify childhood violence as either Intellectual Developmental Delay (IDD) changes that cannot be changed, or as a symptom of a mental health problem that is potentially treatable. If a child falls into DD or both categories, they are usually not eligible for government supported mental health services except for mood disorders such as depression, anxiety or OCD. If the child is covered by private health insurance, they are referred to private practice providers, also in short supply and with high deductibles and co-pays, so many go untreated. In the United States, mental health services are grossly underfunded with a shortage of qualified providers by a 60 % margin.

Below is a suggested list of risk factors that have been suggested covering biological, psychological, family, social and environmental etiologies for aggressive and violent behavior in children. It is not the only way to categorize them however. Due to limitations of space on a huge topic, I will just list the main causes that interferes with normal development and social learning, resulting in aggressive or violent behavior. Afterwards, I will share prevalence of some of the problems, more detail about how certain problems impact aggressive behavior, how US mental health systems and school manage them and suggested solutions.

1: Biological- Brain and physical changes

· Pre-natal Alcohol & other substance use (Fetal Alcohol Syndrome),

. Prescription drugs, smoking

· Genetics

· Malnutrition

· Endocrine & gender differences

· Delivery complications

2: Attachment Problems: Significant disruption in primary caregiver relationship

· Poor, insensitive care by caregiver due to anger, mental illness (ie Post-partum depression), addiction, low intelligence

· Physical, emotional or sexual abuse or neglect

· Separation from primary caregiver or pet by, divorce, death, illness, hospitalization

· Repeated change in caregivers in foster care, adoption process, or institutional living

· Repeated traumatic events or major changes

· Difficult temperament, illness or premature status of infant

3: Disturbed Family Dynamics and Parenting

· Parental mental illness antisocial or drug addiction

· Sex trafficking

· Neglect

· Aggressive or delinquent siblings

· Harsh disciplinary measures

· Poor parental supervision, cold parental attitude, parental conflict

· Disrupted families, single parent, low family income, large family size

· Criminal or incarcerated parent

· Very low income, Welfare or homeless families

4: Direct Exposure to violence and Trauma

· Direct physical abuse or neglect

· Emotional and sexual abuse, rejection

· Observing domestic violence

· War

5: Environmental Exposure to Violence

· Living in violent communities or cultures ie high crime neighborhood of inner-city

· Media and electronic devices with indirect exposure to trauma and EMF waves

· Peer delinquency and gangs

· Racial and gender discrimination

· High delinquency school attendance, or CRT and Transgender instruction

· Poverty

6: Psychiatric, Mental Health, Behavioral Health

· ADAD, ADD

· Mood disorders

· Substance abuse

· Personality Disorders

· PTSD

· Psychotic disorders, Bipolar and Schizophrenia

· Conduct Disorder

7: Neurodevelopmental

· Genetic: Down Syndrome

· Autism Spectrum

· Learning Disorders

· Intellectual Disability

8. Individual Factors

· Temperament: impulsiveness, hyperactivity, risk-taking

· Low intelligence, poor concentration

· Inflated or low self-esteem, lack of empathy, feelings of rejection

· Low school achievement

Prevalence of Developmental Disabilities and Risk Factors

The CDC and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) found in a study that 17% of children aged 3-17 had a developmental disability and that the percentage increased over two time periods compared, 2009-2011 and 2015-2017. Increases were also seen for specific developmental disabilities in the same age group. The specific diagnoses were ADHD (8.5-9.5%0, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (1.1-2.5%) and intellectual disabilities (ID) (0.9-1.2%. www.cdc.gov

Cannabis is the most used recreational drug in the United States, and its use is increasing among children, adolescents, and adults, including pregnant women. The global prevalence of cannabis use in 2017 was estimated at 188 million people, or 3.85 of the worldwide population. The content of THC is currently 2 times higher than it was 15-20 years ago. Up to 25 percent of high school seniors report using cannabis within the last month of studies. Among pregnant women aged 15-44, cannabis use was over 4.9%, rising to 8.5% in the 18-25 year-old age range. Its use among young, urban, socioeconomically disadvantaged pregnant women is estimated at 15 to 28%. Many women believe it is safe to use during pregnancy.

Pre- and post-natal exposure to cannabis may be associated with critical alterations in newborn infants that can last into adolescence. Abnormalities include low birth weights, reduction in head circumference, cognitive deficits (attention, learning, memory), disturbances in emotional response leading to aggressiveness, high impulsivity, affective disorders and higher risk of later substance use disorders. Neurotransmission systems are also affected by cannabis consumption during lactation. There are some confounding assertions about exposure regarding the trimester of use, use of other drugs as well, and whether or not supplemental folic acid was taken.

Stress and alcohol use go hand in hand, and increased during the COVID pandemic. Even before the pandemic, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) was estimated in 2 to 5 percent of schoolchildren. FADS is the most common preventable cause of intellectual disability in the world. FADS can cause complications in growth, characteristic facial features, behavior and learning problems, and overlaps with mental health symptoms. Many variables determine the severity of FADS such as how much a person drinks, rate of metabolism and stage of fetal development. Children with both FAS and partial FAS have deficits with self-regulation, impulsivity, aggression inhibition, executive functioning, social skills and math skills that interfere with school performance and ability to make friends. One notable feature is a gap between intelligence and adaptive functioning. They may appear to be intentionally oppositional. Unfortunately, many children with FADS fall through the cracks in getting appropriate treatment.

School Shootings by Children

Social and moral learning begins in the family at a very early age, with children making distinctions between what is right and wrong, acceptable and non-acceptable by age 3. Social norms must be taught by parents and corrections made for aggressive mistakes. If the parent is not able to do this, or the child does not have normal brain function and cognition, the process will be interrupted. Children need to be taught problem-solving skills and morals at an early age while behavior patterns are first being established and programmed cognitively. Aggressive behaviors not resolved commonly lead to progressively worse expression of domain violations as the child ages. By school age, the social learning arena is expanded to include peers, teachers, and other institutions.

Multiple risk factors influence the development of aggressive, delinquent and violent behavior patterns in children. There are many signs when a child has aberrant social reasoning and moral cognition. By the time a child enters school, aggressive behavior is easily recognized. It becomes a social problem for the community, not just the individual child and family when effective measures are not taken.

Unfortunately, mental health and behavioral health services in the United States is underfunded and understaffed by a wide margin. Even with funding, there are not enough qualified mental health and school counselors. Developmentally disabled children are mainstreamed in schools, meaning that they attend the same classes as children with normal development in classrooms with up to 35 children and one teacher, who cannot possibly give individual attention to any one student. In severe cases, their disability prevents moral and social reasoning, risking harm and educational disruption of other normal cognition students. IDD students are not eligible for full mental health services because their conditions are not amenable to treatment or curable, although depression or anxiety can be treated. If a child with Intellectual Developmental Disability causes disruptions or is aggressive in class, nothing is done to assist the teacher, unless a parent attends the class to help out or the rare school counselor or aid is available.

In the case of the 6 year-old boy who shot his teacher, if he is developmentally disabled, nothing constructive will likely be done. The teacher had previously been asking the school for help with the student, including the day of the shooting when another school employee reported the child had brought a gun to school. His parent was not present at the school that day. Teacher’s aides are sometimes made available for IDD students, but frequently are not available because of low funding, lack of training opportunities and poor wages. The COVID mandates have also limited the willingness of people to even apply for school staff positions. We will never know the whole story. But everyone should be concerned about the lack of care for needy but potentially violent children and its effect on the entire educational system.

What if the boy had a mental health diagnosis? Even if a child is receiving mental health services, HIPPA laws prevent counselors from advising school officials about problems, diagnosis or treatment unless the parent signs a release of information to do so. This interferes with school staff’s ability to address classroom security to protect students and teachers. And as mentioned before, mental health services for children in general is not fully available with long wait times exceeding a year in many locations.

According to my counselor friend, there are also limitations by diagnosis on what is eligible for treatment by county mental health departments. For example, conduct disorder, delinquency, and full spectrum FAS are considered to be largely untreatable brain damaged conditions. No bipolar, schizophrenia or borderline personality disorder can be treated until age 18 in her organization. Oppositional defiant disorder, attachment disorders, ADHD, and depression can be treated. But if a child has more than one diagnosis, usually treatment is directed only at one. Any symptoms noted on intake can only be attributed to one diagnosis.

Solutions

The need for more funding for substance abuse recovery is widely known. Since children’s basic behavior, moral cognition and social reasoning is largely taught by parents and family dynamics, it makes sense that parenting support should be greatly expanded. Good parenting requires skill, empathy, healthy minds and bodies and knowledge about child development. Parent and grandparent support groups could go a long ways towards preventing the problems of childhood aggression. There are two types of groups, either peer-support or curriculum based. Because some many children are raised in day care centers for working parents, more training for pre-school aides would be very beneficial. Trained school counselors school age children who lead weekly programs as part of the curriculum have been have been very successful, but again, funding limits availability for that.

References

Robin J Harvey et al, Social Reasoning: A Source of Influence on Aggression, Clinical Psychology review, Vol 21, No 3, 2001.

Rolf Loeber, Dale Hay, Key Issues in the Development of Aggression and Violence From Childhood To Early Adulthood, Annu. Rev. Psychology 1997.

Nancy G Guerra et al, Moral Cognition and Childhood Aggression, Chapter 2, Aggressive Behavior: Current Perspectives, edited by L Rowell Huesmann, 1994.

Pratibha Reebye, MBBS, Aggression During Early Years – Infancy and Preschool, www.ncbi.nim.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2538723/#sec-18title.

John J Wilson, Predictors of Youth Violence, Juvenile Justice Bulletin, April 2000.

Joseph Murray, David P Farrington, Risk Factors for Conduct Disorder and Delinquency: Key Findings From Longitudinal Studies, The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, Oct 2010.

Kirsten Weir, A hidden epidemic of fetal alcohol syndrome, American Psychological Association, July 1, 2022.

Increase in Developmental Disabilities Among Children in the United States, CDC Web Archive, www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/developmentaldisabilities/features/

Cannabis Use in Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women: Behavioral and Neurobiological Consequences, www.frontiersin.org/articles