Introduction

There are several major, concurrent water war situations in California that will result in either restoration or further destruction of ecosystems. All are impacted by 20 years of drought and warming. Three of these battles include the Bay Delta, the Salton Sea, and Owens Valley and Mono Lake. This article highlights the draining of Owens and Mono Lakes in the Sierra Nevada region that were drained in order to develop and maintain water flow in the Los Angeles Aqueduct with resulting severe, hazardous air pollution. During September and October of 2022, litigation and court hearings were conducted between the large and powerful Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (DWP) and the Great Basin United Air Pollution Control Board (GBUAP), both California state agencies.

History

In the early 1900’s, Los Angeles was suffering catastrophic periods of drought, interspersed with floods from atmospheric rains. Because of its natural semi-arid climate, LA planners and officials wanted a new source of water and conveyance system in order to expand it into the huge metropolitan region that it is today. The mayor, engineers, wealthy investors and media turned to Owens Valley in the Sierra Nevada, along the eastern border of California. This elite group became known as the San Fernando Syndicate. Deceptive measures were used to obtain land and water rights, such LA agents posing as farmers and ranchers. The 233-mile-long Los Angeles Aqueduct from Owens Valley was built between 1905 to 1913. LA remained thirsty, so a 105-mile extension to Mono Lake creeks was added in 1940, along with a reservoir. A second aqueduct was built between 1965 to 1970. All were built by the LA’s DWP and led by its chief engineer, William Mulholland.

Construction of the aqueduct was controversial from the start because water diversions to Los Angeles drained Owens Valley and eliminated it as a viable farming community. The aqueduct’s infrastructure also included a storage reservoir with the construction of St Francis Dam in 1926. The dam collapsed two years later, killing at least 431 people. That led to the formation of Metropolitan Water District of Southern California in 1928 to build and operate the Colorado River Aqueduct to import water from the Colorado River.

The continued operation of the Los Angeles Aqueduct led to extensive public debate, legislation, need for ecosystem restoration, and litigation regarding the negative ecosystem and air quality impacts on Mono Lake, Owens Valley, down wind and tribal communities, and water access. The term California Water Wars came into use after farmers from Owens Valley dynamited the aqueduct several times. The water exports to Los Angeles severely impacted fish habitat, lake levels and air quality. Subsequent lawsuits culminated with the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) requiring LADWP to restore fishery protection and raise Mono Lake back to 6,391 feet above sea level in 1974. That has not yet happened.

However, war and violence in Owens Valley began earlier in the mid 1800’s. There are five indigenous Tribes with historical connections to what is known as Owens Valley. Patsiata is the Indigenous name for Owens Lake. Native Paiutes hunted and farmed along Owens Lake and lush pastures until settlers, protected by US Troops, moved in, stealing their land and water. By 1860 their lands were overrun with cattle and sheep.

During the Owens Valley Indian War, from 1861 to 1866, settlers and soldiers tried to wipe each other out but the Tribes lost. Paiute homes and stores of food were destroyed. Paiutes fought back with bows and arrows, and a few guns. On March 19, 1863, soldiers and white settlers attacked Paiutes who were reportedly killing livestock in the area for food. The battle began in a nearby oak grove and the Paiutes were chased into the lake, hoping to swim to safety. The Paiutes were easy targets in the water and they were shot by the troops or drowned, including women and children. Only two survived. In the past few years, archeologists have found historical remnants from the massacre.

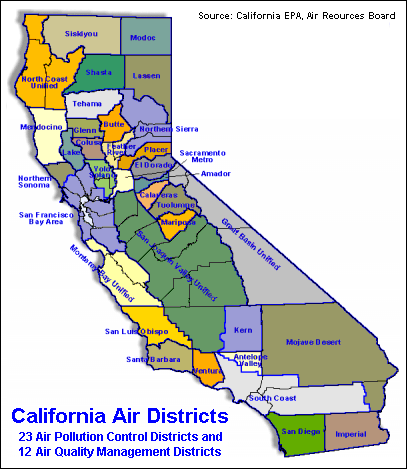

The Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District was formed in 1974 as one of 35 California air districts to collectively develop a comprehensive approach for reducing air pollution. The GBUAP district includes Alpine, Mono, and Inyo Counties, almost 9 million acres and a population of about 32,000 people. The district has 3 branches: the Governing Board, the Hearing Board and the Air Pollution Control Officer. Primary responsibilities are to adopt rules, regulations and policies that govern air quality to meet state and federal mandates, control air pollution caused by the City of Los Angeles’ water diversions, and monitor and mitigate adverse air pollution impacts.

Air Pollution Mitigations and Legal Battles

According to a 2014 agreement, LAWPD agreed to comply with district orders to implement controls on 48.6 square miles of the lake bed and up to 4.8 additional square miles if needed. The agreement allowed use of shallow flooding, managed vegetation, tillage and gravel placement to contain and prevent dust emissions. And under an earlier agreement, DWP must fund 85% of Great Basin’s annual operating budget, about $7 million, and pay for all district legal fees whether it wins or loses in court. LADWP claims it has spent $2.5 billion dollars on dust control measures, all of which have been passed onto water ratepayers.

A portion of the water that was conveyed to Los Angeles via the aqueduct for the first 90 years, must now be directed to Inyo County ranch lease operations, fisheries and other court-stipulated mitigation projects to meet federal air pollution standards.

GBUAP identified a 5-acre parcel on the Owens Lake shore that did not have the required dust controls and was causing significant air pollution from dust storms downwind from Owens Lake. It was not included in the LADWP mitigations because of cultural significance to indigenous peoples. GBUAP maintained that toxic dust with minute sized particles less than 10 micrometers in diameter, PM10, from the 5-acre area was spreading downwind to towns of Lone Pine, Ridgecrest and the Naval Air Weapons Station, China Lake.

GBUAP started levying heavy fines against LADWP, totaling over $1 million. LADWP counter-sued. On September 27, 2022 the Superior Court of California, in the County of Sacramento, ruled that the LADWP did not have to pay the fines, but does have to provide dust mitigation on the area in question.

The prior agreements did not settle litigation over the 5-acre area in question. Part of the dispute is that projects need approval of all five indigenous tribes, but is not sanctioned by one of those tribes, the Fort Independence Indian Community of Paiute Indians. Great Basin argues that the area is not on tribal land and is held in trust by the State Lands Commission, which does support implementation of air pollution controls. The acrimony between the parties was also aggravated in attempts by Los Angeles City Council to dismiss portions of a 1994 agreement to control dust emissions at Mono Lake. Great Basin believes Los Angeles is trying to avoid responsibility for the environmental damage its water diversions have caused. DWP argues that climate change is making it impossible to ensure that dust control can be fully effective.

Summary

This water and air battle is one chapter in the 150-year story of how California has relied upon the building of dams and conveyance systems to convert natural ecosystems and watersheds for total human consumption, control and profiteering. The state uses wealth and power as a weapon against indigenous peoples to confiscate their land and water with little accountability for the negative consequences and destruction it causes. Although the current litigation concerns air pollution from dried out lake beds, the ecosystem destruction, cultural genocide and loss of productive activities such as farming, hunting and fishing is horrific. The images tell a story of total disrespect and mismanagement of the environment. Any yet this story is being repeated in other California regions as well.

Clean air, water and healthy ecosystems are all interdependent and necessary for life on this planet. The mismanagement of natural resources by the California state government is in dire need of correction. Remember this story.

Dear Amethyst

Thank you for your comment. The stories about Owen’s Valley and Mono Lake are very moving for me. I don’t know the story about Brent but will look that up.

Elaine - I just ran across your substack. My family on father's side was from the Owen's Valley and lost their ranch land and Bishop business, due to the diversion of the water to LA. they moved to LA around 1930. (Subsequently, Bishop and Mammoth, still had deep roots for us of my generation, and I have great memories of time spent there vacations and summers.) Thanks for this post.

Have you discovered the very interesting story of Brent, the man who bought Cerro Gordo (famous & historic Silver Mine which literally made LA!!). Close to Lone Pine & Keeler. He is trying to restore the ghost town there. Brent has been at it, going on three years and has a youtube channel documenting the adventure, called "Ghost Town Living". Fascinating to follow! He's a good educator as well.